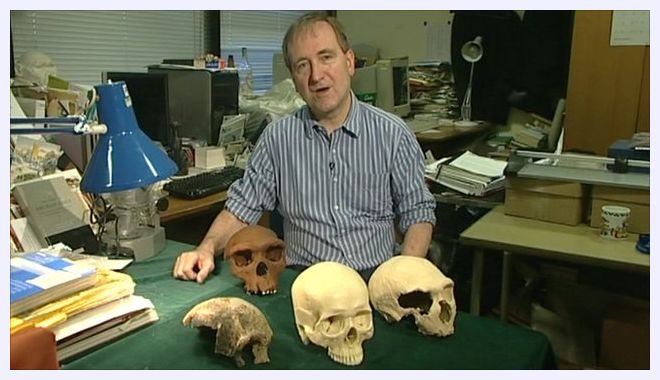

I was robbed twice, and then refused entry into communist Czechoslovakia where the museum at Brno held key specimens of both Neanderthals and Cro-Magnons. It was a great adventure, especially for someone who’d hardly been out of England. My aim was to test that theory by carefully measuring their skulls and the skulls of Homo sapiens and – by using new statistical methods to compare these two versions of humanity – determine whether or not we were descended from Neanderthals.Ĭhris Stringer at a campsite in Yugoslavia, 1971, on the roadtrip that defined his career and changed his life. I drove my old Morris 1000 from London to Bristol and later across Europe on a 5,000-mile journey around the continent, visiting museums in order to compare fossils of ancient Homo sapiens – such as the Cro-Magnons – with those of Neanderthals.Īt the time, the dominant theory of human evolution claimed that Neanderthals were direct ancestors of modern humans.

Palaeoanthropologist Jonathan Musgrave, from Bristol University, offered me a PhD grant, and a month later I embarked on a scientific trip that would define my career, change my life – and help reassess our understanding of humanity’s distant past. I learned a lot but was about to quit academia to become a science teacher when fortune intervened once more. Indeed, I was lucky again when Don Brothwell secured me a temporary job at the Natural History Museum. I graduated in 1969 when there was a lack of research opportunities in my field. There I was shown genuine human fossils, including a Neanderthal skull from Gibraltar.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)